“Lies frequently reveal much about the values of a society, even when the field worker can not check on them.” (Hortense Powdermaker, 1966, Stranger and Friend: The way of the anthropologist, pp. 185-6).

Lies, as stated above, can reveal a lot. Gaining insights from lies – or inaccuracies– aligns perfectly with a Citizen Sociolinguistic view of knowledge. As I’ve mentioned (often) in this blog, whether accurate or not, how someone describes their own language tells us something about what that person believes society values. Someone who describes themselves as speaking “broken English,” for example, may not be describing their own English accurately, but they have identified a dynamic in society that makes them feel insecure about how they speak.

So, as Citizen Sociolinguists, misrepresentations, inaccuracies, and even instances of straight-up lying about language are all important to consider. As observed by Hortense Powdermaker above, lies “reveal much about the values of a society.”

Lies may also be important sources of insight for everyday citizens, especially

What insights can Trump’s lies can give us into our own society and its values?

In the quotation above, Powdermaker was describing her fieldwork in Mississippi in the 1930’s. Specifically, she was describing the disproportionate number of people in white society who claimed to have ancestors who were officers in the Confederate army, or who had owned large plantations and many slaves. While Powdermaker points to facts that show many of those she interviewed must have been lying, these statements, even more so in their inaccuracy, suggest an unapologetic presence of racist values.

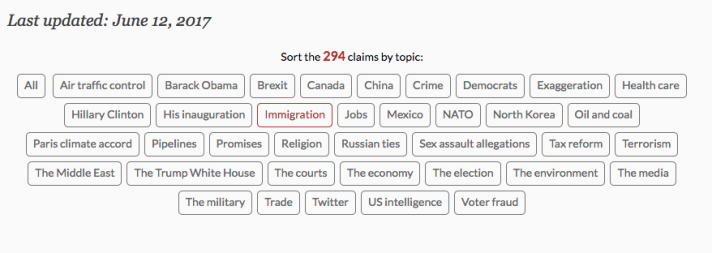

So, let’s consider: What does Trump lie about? What can we learn from those lies? To jog your memory, here is a list of topics Trump has lied about, compiled by the Toronto Star:

A quick glance at this list might bring to mind many of Trump’s lies or misrepresentations: He has lied about attendance at his inauguration, he has claimed he predicted the Brexit vote, he has claimed there was “massive voter fraud” during his election. He has also, notoriously, claimed that President Obama was not born in the United States, he has claimed the Paris Accord would punish the U.S., forcing us to close coal mines while China opens more, he has claimed the Russia-Trump story is nothing but “fake news.”

What can we glean from this lying (yet sitting) president? Obviously, these are claims of a disturbed man who will say anything to put himself in first place. But, do all these lies provide any deeper insight into what our society values? What propelled a liar of this magnitude into the highest office in our country?

Many of the things Trump lies about are not important (It seems foolish to join in the quibbling about how much of the Mall in D.C. was populated with people at his inauguration.) Similarly, the lies that middle-class whites in Mississippi told about their ancestors were not important (Why quibble about how many slaves someone’s ancestors really owned—whether 1, 2 or 10?). However, these types of lies share a similar dynamic: People drawing on fantasies about themselves—and the willingness of others to go along with those lies—inevitably points to a hollowness. Powdermaker suggested that this hollowness, in the case of whites in Mississippi, was an absence of “a middle-class tradition.”

As the gap between super-rich and poor in the United States grows, a similar absence today seems worth considering: There are countless people in the United States –poor, middle-class, and wealthy—who live on fantasies of super-wealth, of fame, popularity, celebrity, the “good life”, or the super-successful-venture-capital-backed start-up. And, many of these fantasies may be as hollow in human values as those of 1930’s Mississippi whites, lying about being from families of plantation owners and confederate officers.

Lies and inaccuracies can be important forms of knowledge, for Citizen Sociolinguists and for just plain Citizens. Donald Trump’s lies are not going to stop. What else can we learn from them?

What is the absence we—both rich and poor—are covering up by living with the lies of our president? How might we fill it with something else?

Wow, this angle blows my mind! During my fieldwork, I was not sure how I could interpret lies. I have been hanging out with some elementary school students and asking them about the languages they could speak and their levels in those languages. Sometimes children lie about what they are able to do depending on who’s around us when I talk to them. The inconsistency probably reflects what he thinks his peers (the “micro-society” the child is located in) value. Thanks for this thought-provoking piece.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great to hear your report “from the field,” Yeting, and thanks for your comment! Looking forward to hearing more about your research soon!

LikeLike