We will be as fair as we possibly can. The smaller people will definitely be handled.

–Diane von Furstenberg, on the fate of her vendors during the COVID-19 downsizing of her wrap-dress empire

All of us have probably at one time either called someone out for saying something offensive, or been called on our choice of words. Calling someone out for their words is awkward and takes effort. It’s a social risk. I call these instances, “citizen sociolinguistic arrests,” those moments when someone feels strongly enough to take that social risk and call deliberate attention to another’s words: “Please don’t call us girls, we’re women” or “I’m Asian American. We don’t really use the word Oriental anymore.” Those on the receiving end of a citizen sociolinguist’s arrest might feel a bit defensive—“I was just kidding” or “it’s just a figure or speech!” or “Sorry, I didn’t realize you were so sensitive!”. Despite defensive remarks to the contrary, when people take the trouble to call us out on the way we use our words, something larger is going on.

This brings me to Diane von Furstenberg, and the statement quoted above, and, most specifically, her reference to “the smaller people.” In case you are not familiar with DVF, she is an aging fashion designer who, arguably, invented the “wrap-dress” decades ago. She is apparently, according to a New York Times profile of her published this week, struggling during the COVID-19 pandemic. While she still carries a net worth of over one billion (and is married to another billionaire, Barry Diller), her business has been losing money for years. And now, with coronavirus, “fashion is out of fashion,” and the wrap-dress mogul is doing even worse.

DVF’s “money problems” seem laughable to most of us. Still, those who work for DVF have had to suffer because of her losses. Bad business for DVF has meant much harder struggles for those who have worked for her, and the article mentions she has had trouble paying her vendors. One $20,000 invoice for a flower order, leftover from an event she organized in 2019, has still gone unpaid. Given her downsizing plans, this floral designer and other vendors may go without their pay, the way of many of DVF’s former employees who have been put out of work by the incessantly shrinking demand for DVF’s fashions, and now, the pandemic. When questioned about how business consolidation might affect these empolyees, Diane offered this explanation and reassurance:

“We will be as fair as we possibly can. The smaller people will definitely be handled.“

Hundreds of readers took to the comment section to take issue with nearly everything about DVF’s travails, and citizen sociolinguistic arrests zeroed in on this particularly telling turn of phrase: “the smaller people.”

Tiago from Philadelphia in a comment that received 275 recommendations (NYT does not do ‘thumbs up’) pointed directly to that “smaller people” statement:

Dozens of others directly called out the reference to “smaller people.” A few examples:

One might argue that these comments remain in the realm of simple word choice, just an unfortunate phrase, “smaller people.” These are “just words” after all. DVF may have been speaking off the cuff. Give her a break.

However, other readers made explicit the very real and strained conditions the “smaller people,” as DVF calls them, are living through now, and the consequences of self-interest of the kind DVF is displaying with her “smaller people” word choice. Some commenters explicitly mentioned themselves as objects of the “smaller people” reference. Those who have been most hurt by COVID-19:

Some explicitly name the suffering of the “small people” DVF is selfishly short-changing:

And some comments even came from DVF vendors themselves, literally those people whom DVF referred to as “smaller people,” like Rob Adler, still owed $9,000 which he will probably never see:

Sometimes, people believe that getting called out for our words is just a matter of political correctness. We should instead pay attention to deeds. But, when a billionaire complains about her own personal financial struggles and refers to those she is shafting as “smaller people,” we can see how her words themselves are deeds, creating the unexamined life she lives, a life in which she doesn’t see the people who work for her, who count on her for their living, as equally important humans. These citizen sociolinguistic arresters aren’t just wordsmiths taking issue with the phrase “smaller people.” These are real people commenting on these words because they construct a world where DVF feels little responsibility for others—the florist who was stuck with the $20,000 bill, the printer who will never be paid $9,000 owed him by DVF, and those who will never be paid severance wages owed them.

In their sheer accumulation, these comments become the real news story, bringing the blunt reality of DVF’s way of doing business to light. While the headline of the article reads, “Diane von Furstenberg’s Brand Is Left Exposed by the Pandemic,” nobody in the comment section is lamenting the degradation of the DVF brand. The hundreds of comments nearly unanimously condemn her selfishness in the face of COVID-19. The preponderance of this view is so strong that, rather than raising the same issue again, some comments simply call attention to this accumulation of remarks taking DVF to task:

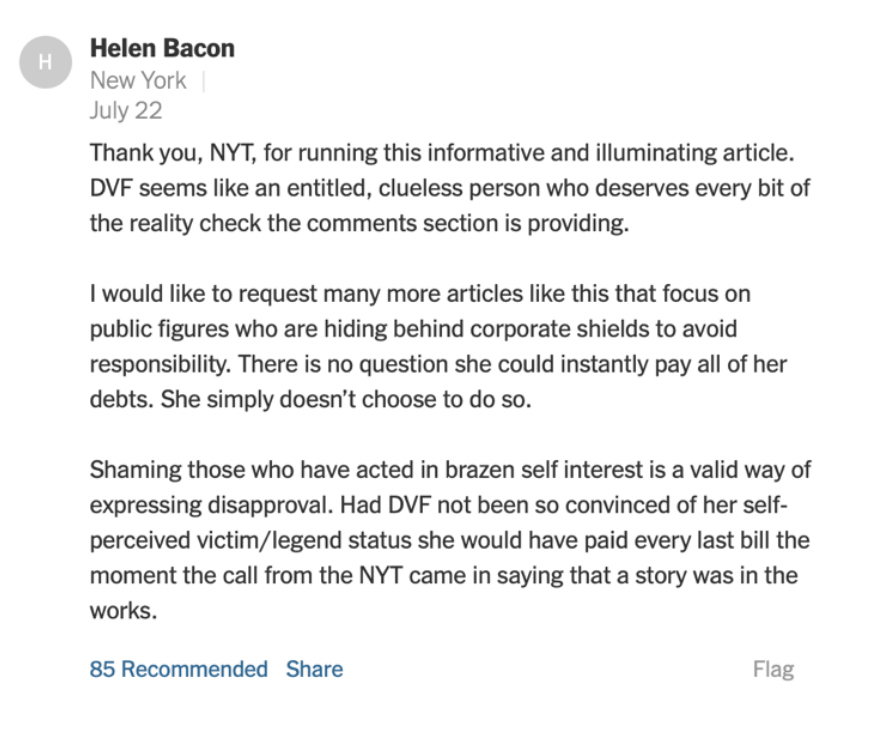

Another response similarly comments on the comments—praising the New York Times for the article, and complementing “the reality check the comments section is providing”:

It’s hard to tell whether this commenter is being sarcastic with their big “thank you” to the NYT. It’s also impossible to say whether the author of the NYT article was intentionally outing DVF as a woman of “brazen self-interest.” That seems unlikely. However, that’s the message this article is delivering—driven home as a result of the contributions of these active readers (and citizen sociolinguists), who have called out DVF’s language and the stance it conveys.

By engaging in these online citizen sociolinguistic arrests, these commenters haven’t just shamed DVF for her use of language. They have shamed her for the entire way of life her language choice conveys and reenacts. Collectively, they ask, “Why, DVF, do you call your vendors, “smaller people”? We know those people, we are those people, and our lives are important, not small.”

Citizen sociolinguists’ arrests may at first strike people as trivially focusing on simple words, but these acts call attention to broader social conditions: Calling some humans “smaller people,” like repeatedly referring to grown women as “girls,” or misguidedly greeting an Asian American who grew up in Ohio with the Chinese language greeting, “ni hao,” are not simply problems with word choice. They both reveal and reproduce unexamined social relationships. The speaker of those words enacts their own unexamined stance again and again through their language choice—until they are faced with a citizen sociolinguistic arrest. A citizen sociolinguist’s arrest has the chance of starting an important conversation, a slim chance of pushing the utterer of each of those poorly chosen words to start speaking differently, and in the process, to start building a different way of seeing and acting in the world. By using words in a new way, one learns something about another person’s perspective, and may even develop compassion for those they don’t know or even understand.

It may be too late for DVF, but her commenters have raised the awareness of the absurdity of profiling her in the NYT. These citizen sociolinguists changed the story from one about the fashion business, to one about people. Comments from those who have been hurt by DVF’s world view, who have experienced hurt from others who share the world view that sees some humans as “smaller people,” may have pushed some readers to think differently about their own stance toward inequality during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

Have you engaged in “citizen sociolinguistic arrests”? Have you been a recipient of one? How did those encounters change your view of the world? How do words display—and produce—compassion or lack thereof? How can we guide each other to become more understanding in how we use words, and in how we show compassion for each other? Do you think we can? Please comment below!