Lately, the Internet has become an indispensable resource for teachers and professors as we surf through websites and social media looking for examples, links, lessons, or just something to break the ice, lighten the mood, and remind us all of our shared humanity while online.

While searching, we might also discover a secret that most avid Internet-surfers already know: The Internet can make online learning productive, fun, individualized, human-like, illuminating, and even important. To that end, I dedicate this post to just five online language games—five of the infinite ways the Internet invites us into moments of language wonderment. As you engage in these naturally occurring language games, you may think you’re “just” surfing the Internet, but, I guarantee, online learning will happen—to make that more obvious, I’ve titled each of these games with an important mini-lesson about language you will learn as you partake, and added some post-game reflections for online learning bonus points:

Game 1: Words Create Our World—The Caption Game

This is probably the most “classic” of all language games, created by the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who famously coined the term “language game” to describe everything we do with words.

Examples: This picture was first used by Wittgenstein to show how language shapes our world. So, what is it?

If I tell you this is a “duck” you probably see the image one way. If I tell you it is a “rabbit,” then what do you see? A rabbit? Wittgenstein used this ambiguous image to illustrate how the words we use create the world we live in.

This ingenious demonstration of the power of words can be illuminated in many ways. Internet surfers can find similar examples (multiplying like rabbits) online. The famous “Rubin vase,” pictured below plays a similar game with viewers and language users:

Another well-known example, this image of a “young lady,” takes us into the realm of the uncanny. What—in addition to the young lady—do you see here?

Are you stumped? In both these examples, it might be easier to see the unnamed image if someone captioned it for you: In the “Rubin vase” image, do you see “two faces” in addition to the vase—once you read those words? In the “young lady” drawing, do you also see an “old woman with a wart on her nose”—if the picture is captioned that way?

I think these pictures are cool, but if they strike some readers as old, stuffy, and esoteric, consider this more up-to-date observation: We play the same language game any time we caption a photo for Instagram or Snapchat! To illustrate, this cat picture (or any cat picture), might be described in infinite possible ways:

I could caption this “Cat on a loveseat” or “Cat contemplating the meaning of life” and viewers may see this photo very differently depending on which of those descriptions accompanied it.

Play! Now that you’ve seen a few examples of how words create our world, go ahead (if you haven’t already!) and search around for more of these ambiguous images online. You might start by looking for “optical illusions.” See how the words you use to describe each picture can change what you see! Then try playing with some of your own photos on social media. How do you turn the image into a certain kind of event by captioning it one way or another? (“The Life of The Party”? “My Annoying Brother”? “Dinner with Friends”? “The Last Supper”?)

Reflections: Lately, in the age of COVID-19, using language to talk our reality into being has been a staple on Zoom or other video-conferencing media. If we call the now-familiar Zoom grid-of-faces a “Graduation,” that’s what it is! Call it “Happy Hour” or a “Celebration” and participants will see it as such. In this way, Wittgenstein (and now the Internet) shows us that language is not just a collection of words that describe things, but itself a collectively created “form of life.”

Game 2: Translation is Not a One-To-One Language Mapping—The Song Lyrics Google Translate Game

As The Caption Game above illustrates, words don’t have a one-to-one correspondence to reality. Nor, as this Song Lyrics Game will illustrate, do they have one-to-one correspondence to the “same” words in other languages. Just like a caption for a picture, a translation of a passage will also, always, involve some selection and interpretation. The interpretive nature of translation becomes most obvious when we try to learn a new language—and particularly when we try to fudge a little and use Google Translate instead.

Examples: Language teachers across the globe have tried to impress upon their students this simple fact: Google Translate is not the best shortcut to language learning. And, social media have provided us with some of the best “teachable moments” for this lesson. For years, the Youtube site “Translation fails” has been posting google translations of songs. By running English-language song lyrics through Google Translate, transforming them into many different languages, and then back into English, this YouTuber arrives at silly—and oddly illuminating—results. Her first smash hit was the Frozen lyric, “Let it Go!” After she ran this song through several languages on Google Translate and then back to English, the inspirational “Let it go!”refrain had transformed into the more defeatist, “Give up”:

Updating for new songs and styles, the same YouTuber has now come out with another viral success, based on Billie Eilish’s “Bad Guy” hit, in which the dark and gloomy incantation, “I’m the bad guy,” punctuated by the now-infamous, “Duh,” transforms to “I’m biscuits. Huh?”

Play! Now try it yourself. Take a verse from your favorite song and with the “help” of Google, translate it into a few different languages. Then translate it back to English. What do you get? Keep going until you get the funniest version, then entertain yourself by singing this out loud! Record it for your friends. You might even want to post it on YouTube! What sort of comments do you receive?

Reflection: Translating with Google to surprise yourself with the silliest possible lyrics can be a blast. It’s also a great illustration of how impossible it would be to line up the world’s languages word-to-word to create precisely the same description an object—or each other. Each language seems to do things a little differently. And given Wittgenstein’s observations about language as a “form of life,” this makes sense: Why would we expect words from different languages to line up one-to-one when words don’t line up one-to-one with anything else they are supposed to describe? It’s precisely this slippage that makes language a shared accomplishment—and not a code that a computer algorithm could understand or recreate.

Game 3: Appearances of Linguistic Accuracy can be Deceiving—The Magic Bilingual Idiom Game

As the Song Lyrics Game above illustrates, there is often some slippage between one language and the next—and between any word and whatever it is attempting to describe. As literary theorist Jacques Lacan would put it (but in French), there is an “incessant sliding of the signified under the signifier”. There is no one-to-one alignment—either between language and things or between one language and another language. For that reason, if we translate through enough different languages, and then back to English, we can arrive at “I’m biscuits” from “I’m the bad guy.” But this slippage gets even more mind-bogglingly wonderful when Google Translate does arrive at a translation that looks right, but still doesn’t work! Revealing this invisible slippage, puts the “magic” in this Magic Bilingual Idiom Game, drawing attention to the often-overlooked aspects of linguistic knowledge that multilinguals hold.

Examples: One of the best types of idioms to entertain ourselves with on Google Translate might be those phrases for collections of things: Herds of horses, packs of dogs, clutches of owls, pods of dophins, etc. Often, different languages have different expressions for these.

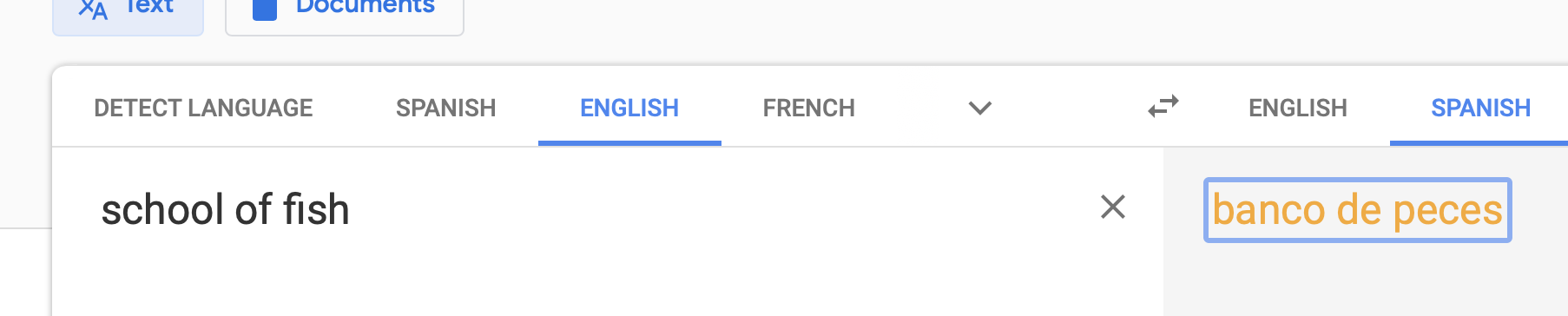

What’s called a “school of fish” in English, for example, is called a “banco de peces” in Spanish. But what happens if we enter “banco de peces” in Google Translate?:

Of course. Banco=Bank, de=of, Peces=Fish. The individual words are translated “accurately” enough. But the resulting expression makes no sense. Bank of fish? How can we ever fix this error? It would be confusing to a monolingual English speaker if a monolingual Spanish speaker were to use the expression “bank of fish” for “school of fish”. And, it would be confusing to a monolingual Spanish speaker if a monolingual English speaker used “escuela de peces” (school of fish) for “banco de peces”. But if two bilinguals used these translations, they would likely know what each other were talking about. Their invisible multilingual knowledge would reveal itself!

Google recognizes that their translation app needs the wisdom carried within bilingual users to hone its functionality—this is a form of bilingual expertise that computers alone could never learn. Therefore, Google has built a feedback tool into their translation tool: Click on Google Translate’s dropdown menu and it will offer alternative translations and even a chance for you to “improve this translation.” You can select the best translation and it will be transformed on your screen, just like this:

If you care to contribute to the human improvement of Google Translate, calling on your own multilingual expertise, chime in, and Google Translate will get better.

But even if humans improve infinite entries in Google Translate this way, the app still will not work perfectly. Many expressions and their translations simply cannot be fully illuminated through a computer app. Consider, for example, the French expression, “cherchez la femme.” Like “bank of fish,” this sentence translates easily in a one-to-one, faux-accurate way, but it loses much of its resonance along the way. I learned the phrase, “cherchez la femme,” many years ago from a friend in Hollywood who had spent a few years in Paris dubbing movies for a living. He loved saying “cherchez la femme,” and I soon came to get a vague sexist feeling from it. When I asked what it meant, he would give a long, meandering explanation about “noir” movies and how any mystery can be explained by finding the woman at the bottom of it. Knowing no French at the time, I just learned the phrase as a chunk that sounded something like “shayrshayl’phahm” and came to associate it with heartbreakingly sexy French women and intrigue.

Only many years later did I look the phrase up on Google Translate, which conveniently gave me the word-for-word translation, “look for the woman”:

And, the simple, “look for the woman,” translated right back into “cherchez la femme”:

On the day I learned that “shayrshayl’phahm” simply translated to “look for the woman,” (and vice versa) I was a little disappointed. It seemed so mundane. But, it was also inaccurate. The simple, faux accuracy of word-to-word correspondence conceals the different forms of life these expressions create in English or French. That’s precisely the magic of the Magic Bilingual Idiom Game: It reveals all the important aspects of living through multiple languages that the faux accuracy of one-to-one translation conceals. Consider how important precisely this knowledge would be in the context of The Caption Game (above)! Captioning a photo with “Look for the woman” would lead to a very different viewing experience than would “Cherchez la femme”!

Play! Now it’s your turn to try out your own multilingual knowledge. Think of an idiom you know in one language—then, using Google, translate that into another language you know, then translate it back. How does that work for you? Often, you may get the exact same expression. But how do you know whether it has the same meaning? In this game, you will need to call on your own invisible multilingual knowledge (and possibly that of your multilingual friends) to check the layers of meaning and precisely how or if Google Translate fails you.

Whenever you sense something amiss, try to fix Google Translate a little and click on their dropdown menu to “improve this translation.” Of course, with expressions like “cherchez la femme” this might be more difficult. Fortunately, not all human knowledge can be reduced to a Google algorithm! Take note when this happens, revel in your own multifaceted language expertise, and share the good news with a friend.

Reflections: Expressions like “cherchez la femme” render Google Translate almost pointless—but they also serendipitously illuminate the magic of language and the power of multilingualism. Because Google attempts to translate even socioculturally complicated expressions in a one-to-one way, a person needs to know multiple languages and the forms of life they invoke to be able to know when Google Translate leads them astray. For this reason, Google translate is always soliciting feedback from its users. And, over the years, it gets better! Now, it translates many idioms without using a one-to-one correspondence because it has been drawing on the everyday expertise real multilingual people have volunteered—and which you may have already contributed to by playing this game!

Game 4: Subverting Genre Expectations is Funny—The Fake Amazon Reviews Game

Mistranslated song lyrics (like those we’ve played with in the Song Lyrics Game) come off as funny or absurd because they subvert our expectations for the genre: When we expect a dark incantation like “I’m the bad guy” and get “I’m biscuits” instead—we just have to smile. A similar happy twist occurs now and then with the Amazon product review genre. Even though we may doubt the veracity of many of these reviews, we tend to read them in hopes that most contributors sincerely report the facts: If this is a good product or an awful one, reviews will say so. Precisely this practical expectation for the honest and earnest review on Amazon makes fake reviews a brilliant departure.

Examples: You may already be familiar with one of the biggest magnets for fake reviews, the Hutzler 571 Banana Slicer, pictured here:

The reviews of the banana slicer have far more feedback than reviews of any other product on Amazon I’ve seen. Over 58,000 readers came across the review below and “found this helpful”!

After all, who hasn’t for decades “been trying to come up with an ideal way to slice a banana”?

The sociolinguist Camilla Vasquez has written extensively about satirical online reviews like these, and just recently she alerted me to another comic product review for a popular commodity in our age of quarantine: Yeast. This very enlightening review rose to the top:

Play! Now, try to find another “fake” review! What language game is it playing instead of sincerely reviewing a product? Poking fun at that product? Practicing PUNmanship? Venting about another topic? After combing through these and having a few good laughs, pick a product you want to review and try your hand at the “fake review” genre. Go ahead and post it and see how the world responds!

Reflection: For me, fake reviews are life-and-language-affirming. They affirm that people care about enjoying language and a few laughs with fellow humans more than diligently buying and reviewing whatever product crosses their screen. Sometimes the act of sharing one’s sense of humor with the world provides people with more satisfaction than simply consuming that world!

Game 5: We Live in a World of Others’ Words—The Word Wonderment Game

If you’ve been playing all the games above, you may by now be feeling flush with the power you wield with your words—the power to create a world, but also to genre-shift and tear it down! You may also feel humbled by the shape-shifting quality of those same words and our inability to pin down their meanings. Words are indeed powerful, but they also belong to no one person. And no dictionary or reference tool or app like Google Translate can provide a word’s decisive meaning. As the literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin has written (but in Russian), “We live in a world of others’ words.” The Word Wonderment Game is about exploring how our words take on new meanings when others take them out into the world and all its diverse forms of life. The Internet is made for this type of exploration.

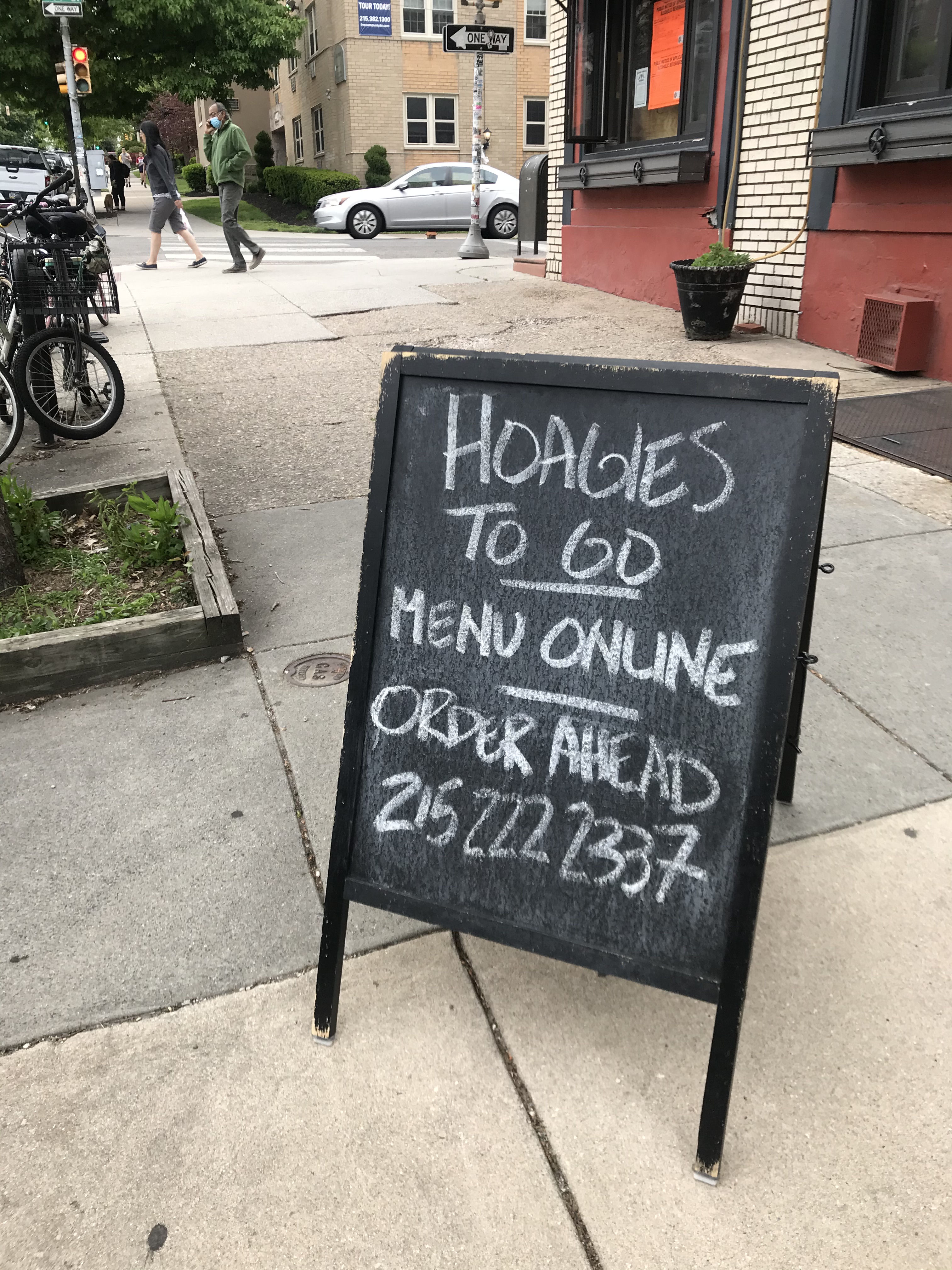

Examples: You can start the Word Wonderment Game with any word or phrase you’ve heard lately that captured your fancy. It may be something new you overheard from teens (“soft girls”) or college kids (“natty light”), a new word for the age of COVID-19 (“face covering”) or a local word you’ve overheard and think you understand by never really fully “got” (“jawn”?). You might even see an intriguing word chalked up on a sign at your local bodega. “Hoagie” for example, is often used in Philadelphia as if everyone knows what it means—and as this picture shows, Philadelphians are venturing out to pick up freshly made hoagies even during quarantine:

But what if you were new to Philadelphia and you didn’t know this word? Or what if you’ve lived here forever but simply want to explore how other people use this word? Via the Internet you can take a shortcut through the world of others’ words. Start with a google search:

Already, Google’s dropdown menu suggests we’ve entered a world in which people associate hoagies with comfort (“haven”) and immediate gratification (“near me”). The list of links proffered next offers solid indications that Philadelphia is hoagie-central. Next, urbandictionary.com provides a selection of strong opinions, and the “top definition” offers more information about the history of the word itself:

A life-like quote in the second entry mentions that you can get hoagies at “da Papi store”:

And this entry authoritatively mentions an exception: “meatball” is the one filling that requires “sub” or even “sandwich” and not “hoagie” as the sandwich word:

These entries and the dialogue included, may set you wondering: Do I even know how to say the word “hoagie”? To explore, head to YouTube, with a new prompt: How to say “Hoagie”. You’ll get a long a boring tutorial—but you’ll also find many other videos in which “hoagie” is under discussion.

After this, you might find yourself reading about “The Great Hoagie Debate”, and even filling out an online poll about it (I admit it. I voted “yes”):

As you churn through these different perspectives on hoagies, you’ll likely also encounter more words you’ve never known before. Wawa, hero, meatball sub, da Papi store, and so on. You’ll also start feeling like some people in Philadelphia really care about hoagies. A lot. It’s not just another word for sandwich. The word “hoagie,” like any other word, is no one person’s alone to define or wield—but one shape-shifting word among many in a world of others’ words.

Play! You may be spending more cross-generational time in conversation these days. This means you may hear new words you don’t often (or ever) use yourself—but that people you know may care about a lot. Ask about those words! What do they mean to the speaker? In what situations would they use them? Inevitably, you will be running across unfamiliar words everyday (“namean?”). Or familiar words that have taken on new meanings (“face covering”). Follow up on those words! What “forms of life” do they invoke? Who uses them? What do they tell us about society? Surf the Internet to find all the nooks and crannies these words inhabit and the ways their meaning changes across contexts. “Slippage” between words and meaning doesn’t only occur when we’re using google translate. Even the word “hoagie” has an indeterminate meaning. So be sure to look into all the different ways our world is made up of others’ words.

Reflection: The Word Wonderment Game revels in the fact that any time we speak, we are participating in a world of others’ words—and others’ perspectives. As you learn about different words and about the forms of life that surround words you thought you knew, you’ll likely run into controversies. You may find yourself feeling strongly about the use of certain words. You may feel that certain words should not be used. Why not? Our strong feelings about words can lead to important conversations about our differences. Through these conversations about language, we can also collaboratively build new meanings together, so that we live in a shared world.

Now, next time you’re on zoom, teaching a class, or celebrating the end of the week, “share your screen”! You may be able to play some of these language games with others and spark more talk about language—in the process, you’ll be collaboratively shaping the world we’re inhabiting, both online and off.

Please share your reflections on any of these games below. If you want more language games, let me know! There are many more that I cut from this short list. What other language games do you play on the internet? Please share!

happened on the card with the alphabet and learned how to spell our name, or to sign a few top secret words to friends. But after a first enthusiastic burst, the card gets lost, the signing seems like too much effort.

happened on the card with the alphabet and learned how to spell our name, or to sign a few top secret words to friends. But after a first enthusiastic burst, the card gets lost, the signing seems like too much effort.

How did Nyle respond? This seems like an important test of not only Deaf communication, but communication in general. According to a sign language interpreter friend of mine: “Nyle did apologize, saying he did not mean to take over and use his fame to overstep boundaries, and I don’t think this tainted his overall reception in any way.”

How did Nyle respond? This seems like an important test of not only Deaf communication, but communication in general. According to a sign language interpreter friend of mine: “Nyle did apologize, saying he did not mean to take over and use his fame to overstep boundaries, and I don’t think this tainted his overall reception in any way.”

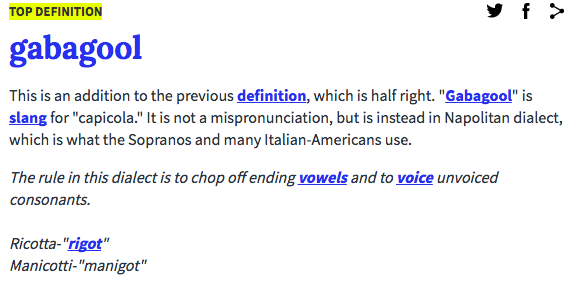

A couple weeks ago, I saw the item “gabagool” on the menu of a local Philly restaurant. Having lived in Philadelphia for a while, I had the vague feeling this was just an ironic nod to the way people here pronounce the delicious, ham-like meat, “Capicola.” But, since it was printed out on a real, official menu of a nice center city restaurant, I thought I might be mistaken. Maybe “gabagool” was just one more variation on Italian meats and cheeses that I didn’t know.

A couple weeks ago, I saw the item “gabagool” on the menu of a local Philly restaurant. Having lived in Philadelphia for a while, I had the vague feeling this was just an ironic nod to the way people here pronounce the delicious, ham-like meat, “Capicola.” But, since it was printed out on a real, official menu of a nice center city restaurant, I thought I might be mistaken. Maybe “gabagool” was just one more variation on Italian meats and cheeses that I didn’t know.

features of a scene that go into using the word “gabagool.” The most popular video example, by far, is

features of a scene that go into using the word “gabagool.” The most popular video example, by far, is

Have you ever tried crossposting?

Have you ever tried crossposting? more generally. Crossposting—and its ramifications—as a metaphor for communication seems worth considering. What happens when you “crosspost” across the various social groups you are part of? Being completely oblivious of the participants and audience in each of these groups seems socially naïve—at best. And, this seems to be what happened at Yale last month, when professor Erika Christakis notoriously posted, to a college house e-mail listserve, the idea that Halloween is a chance to be “a little bit obnoxious,” countering the campus-wide e-mail suggesting students be sensitive about Halloween costumes (and, for example, avoid blackface). Bringing up the value of obnoxious Halloween costumes might be a nice debate on one of prof. Christakis’ “social media platforms”—say dinner with like-minded colleagues—but, as it turns out, it may be a dumb thing to crosspost to hundreds of Yale freshmen.

more generally. Crossposting—and its ramifications—as a metaphor for communication seems worth considering. What happens when you “crosspost” across the various social groups you are part of? Being completely oblivious of the participants and audience in each of these groups seems socially naïve—at best. And, this seems to be what happened at Yale last month, when professor Erika Christakis notoriously posted, to a college house e-mail listserve, the idea that Halloween is a chance to be “a little bit obnoxious,” countering the campus-wide e-mail suggesting students be sensitive about Halloween costumes (and, for example, avoid blackface). Bringing up the value of obnoxious Halloween costumes might be a nice debate on one of prof. Christakis’ “social media platforms”—say dinner with like-minded colleagues—but, as it turns out, it may be a dumb thing to crosspost to hundreds of Yale freshmen.