Citizen Sociolinguistics flourishes in those moments when language catches us by surprise and forces us to start talking about it. Consider, for example, the way people alternately marvel or reel in horror at the language of teens. There’s something intriguing going on with teen language that sparks human curiosity. Parents and high-school teachers like to share their stories about the language of teens, and professional linguists like to study and explain it. Non-linguists may judge teen language as right, wrong, or just plain weird (“sick” is a word for something you like?). Linguists tend to describe teen language as playing an important and complex role in language change over time (semantic reversal! Sick!). Now, I would like to consider how teen language changes more than just language, it changes world we live in. To get a bigger picture of what teen language is good for we need to turn to a third view: that of teens themselves.

Everyday Adult Perspectives on Teen Language

First, let’s consider how everyday adults talk about the language of teens: Sometimes with wonder, but also with trepidation, even revulsion!

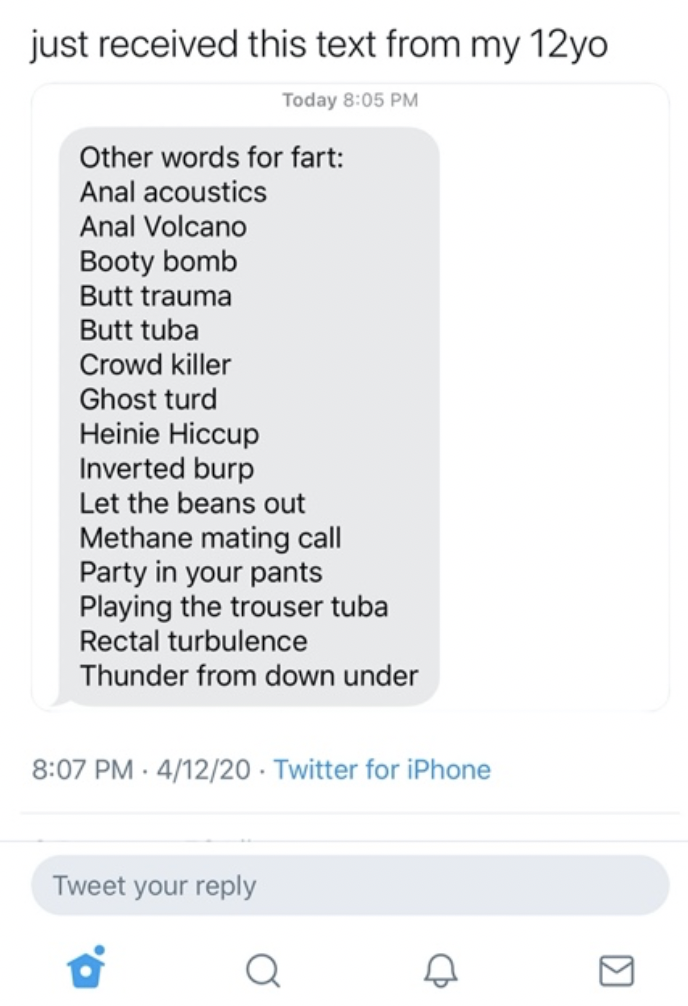

Much of the language of teens seems to crop up out of thin air. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when we have all been at home working, studying, or goofing off together, we may be hearing and seeing more teen language. This post on Twitter, for example, illustrates one working-from-home Mom’s experience with Teen language (or in this case, a 12-year-old):

First of all: Ew! Moving beyond that initial reaction, I showed this tweet to my 13-year-old daughter and she was very impressed! She was also slightly baffled: How did this kid come up with all these different expressions? My daughter and I shared a moment of wonderment (and horror) at this mini fart thesaurus. Sometimes the language feats of teens carry an impressive ‘air’ of mystery and the unknown.

More comprehensive catalogs of teen language or ‘what kids are saying these days’ often lead to this same kind of wonder and disgust. Each semester, for example, my friend Mr. Z, a high-school teacher, has his Language Arts classes compile lists of their favorite “slang,” from which he creates a word cloud. Those words mentioned more often (like “bae” below) show up larger in the cloud, and those less-common words (“sick”) are tiny.

These word clouds have become an impressive tradition over the years, and they’ve begun to function like semester-to-semester time capsules. Each year, the teacher and I, and the crops of new students in his classes, marvel at the old standbys and the new arrivals. These word clouds tend to impress everyone—including other teachers in the school. But as often as people are impressed with teen language, they are baffled, and even wary of it. Sometimes we don’t even understand what teens are saying (BAE? shawty? krunk?). When we do understand (or think we do), we might not know how to react, or how to talk about it (white girl wasted?). Many adults tend to disengage when teens talk in strange ways. What are we supposed to say? Should we tell them not to use those words? To speak with more maturity? More formality? Some teachers would balk at compiling a word cloud like the one above—it seems too subversive for school. And in moments of frustration we might even think, what is wrong with teens? 15 fart expressions? Really? Why can’t kids just speak about important things and do so like adults??!!

Linguists’ Perspectives on Teen Language

Linguists, however, love to talk about teen language. But, unlike many parents, teachers, or everyday language police, they don’t judge it or fear it, they describe it and provide the long view. Still, they often manage to take teens’ active engagement with words and the world out of the equation, describing youth language in general as an engine of language change, rather than exploring teenage talk as a dynamic part of their interactions with others.

This article, posted on the website of the Linguistic Society of America (LSA), for example, points out that, much as some adults would like to limit our language to one, correct, immutable, and testable form, the only thing constant about language (paradoxically) is change. Many words and expressions we take for granted were once considered problematic youth language. The article provides useful examples: “Bus” was once considered an unseemly shortening of “omnibus.” And, many phrases we now consider problematic in certain contexts –the inevitable “double negative,” for example—were once a staple of older forms of English. Linguists are very good at illustrating that language change happens and that it’s okay. No need to worry about teen language—it’s natural. Teen language, like a slowly moving glacier, may be hard to navigate for us old folks, but just as that glacier carves out a beautiful and lush valley, teen language will slowly manipulate the word for us, over time shaping the very language we inhabit and enjoy. Trust the process.

Thoughtful people like teachers and parents who really don’t want to unnecessarily criticize teenagers, find these linguistically informed verdicts on teen language a relief. After discussing controversial words that appear in the language cloud, for example, words that teens themselves have shared, Mr. Z and I want to have an adult message for students, but we don’t want to be preachy. It’s useful to be able to cite linguists who tell us there is something important and lasting going on (language change) when, for example, teens say “like” in every other sentence, seem to shorten perfectly good greetings to “yo,” “what’s good?” or “whaddup?”, or use LOL incessantly, LOLOLOLOLOLOL. They are not being lazy or losing their mental acuity. The linguist says it’s fine. “LOL” in spoken discourse might one day be used by heads of state. Our language will never stop changing and that’s okay.

I’ve always found these explanations useful and persuasive at first, but ultimately incomplete. Once we’ve been consoled by Linguists that teen language is simply contributing to the inevitable if glacially paced process of language change, the conversation usually stops. But when we discuss the role of teen language this way, we take the teens out of the world that stimulates and inspires them, and, out of a world that might also hold injustices and frustrations to which they are reacting, out of institutional norms that they might be resisting by using language in creative new ways. Out of the realm of controversy. Instead of engaging with any of those possibilities, once we legitimize the way teens speak by naming its role in “language change,” we can go back to just waiting for teens to either talk like adults, or for teen language to be accepted sufficiently over the course of time so that adults use it too.

By stepping beyond the “language change” explanation, I’m not trying to debunk anything linguists have learned and published about language change. It’s real. It’s interesting. And it seems important to remind ourselves that language change is inevitable, and that we are all participating in it. However, the focus on language change illuminates only a small corner of a much larger conversation that we can have around teen language. Recognizing that language changes and teen language plays a role the process should be just the beginning of that conversation about language. However, many times I’ve witnessed the “language change” explanation as the end point. Science has spoken. The Glacier will move. Language will be fine. Conversation stops. As an alternative, to keep the conversation going, and to capture the remaining 99.9% of what motivates teens when they communicate, I’m suggesting that when we talk with teens about their language, we include their perspectives as well.

Teen Perspectives on Teen Language

Teens, perhaps more than any other age-group, are surrounded by new and varied language everyday – language of parents, friends, teachers, coaches, multiple and diverse social groups, and, now, the Internet! While many teens may try to act sage and bored, the world and the language that constructs it, is relatively new to them, and one of their main jobs as developing humans is to figure out how to make it work. This will lead to language change. But the language of teens will inevitably change not only language, but also the world. Teens grow up in a world of stimulating newness. Teens also have ideas and desires of their own. Their job is to listen to and participate fully in that world of language. Some of the things they say will seem weird to adults. Sometimes the language they use will change the world.

Consider, for example, the phrase, “people who menstruate.” Recently, this phrase was quoted with disdain by JK Rowling in a now infamous tweet:

Following this tweet, the Internet broke out with horror at JK Rowling’s statement. Many long-time JK fans officially pronounced their Harry Potter Fandom dead. I was confused. As a cis-gendered woman, literally the same age as JK, I thought her comment only slightly funny—a dumb, slightly mean joke—but I didn’t see how it caused such a revolt against her. Then I asked my daughter (13-years old and a big Harry Potter fan) what she thought. “I can see why people are upset. People are rightly calling her transphobic, mom,” my daughter said immediately, and then proceeded to explain to me that many “people who menstruate” might not label themselves “women.” In that moment, we seemed to come face to face with generational differences in language use, specifically how we use language in gendered ways. Who knows if this usage will lead to lasting language change. But discussion of this phrase and how we describe gender categories, seems important. As my daughter’s quick response to my confusion showed me, teens are participating in those discussions and they hold strong opinions.

I raise this example to illustrate the importance of conversations about language—and often, especially, the language of young people. Teens are not just talking about farts, sex, or getting stoned. But that’s part of the picture too, and to talk about the world-changing words, we need to be more open to talking about all language. What if, instead of chalking up the profusion of creative teen language exclusively to language change, we kept the discussion going? We could start talking with teens about the language they use, learning from them what those words are doing, asking teens questions about their language, rather than giving them explanations from linguistics: How did you learn all those words I don’t know? Where do you think they come from? Would you use those words with adults? If not, then with whom? Why? Why do you feel so strongly about using or not using certain words or turns of phrase?

Over the years, I have learned that teens have strong opinions about language—and less strong feelings about whether they contribute to language change. I’m suggesting we listen to those strong opinions. Once we assume teens participate actively in the world of language around them, we might also learn more about the world they live in, the way that they are processing it and in turn shaping it with their language. Then, we can start to think about how they might learn to navigate new and different ways of communicating they will encounter over their lifetime. The social world, inevitably, provides an abundance of opportunity, ridiculousness, oppression, joy, fear, despair, and hope for all of us. Our language is the primary way that we, over a lifetime, make sense of it, and sometimes rebel against it or create it anew, together. Over time, language will indeed change. In the meantime, let’s talk about it and make it work for us!

What kinds of teen language exists in your life? How do you make sense of it? What have you learned from talking to teens about language? Maybe you are a teen? Please comment below.