I am willing to bet a Wawa Hoagie that you (or your “close friend”) have a strong opinion about some aspect of language. By simply googling a bit, browsing through urban dictionary, or candidly recalling a conversation you’ve had recently, some opinions like these might surface:

- If you live in the USA, you should speak English.

- The way people from Philadelphia speak is completely different from the way people from New York speak.

- The Welsh language is amazing.

- The street spelled “Passyunk” should be pronounced “Peah- Shunk.”

- “Jimmies” NOT “sprinkles.”

- People SHOULD NOT use “literally” in a figurative way

- “Ain’t” is not a word/ “Ain’t is a word.”

- Everyone SHOULD learn another language.

- Irregardless is a pretentious way of saying regardless!!!

People have their opinions.

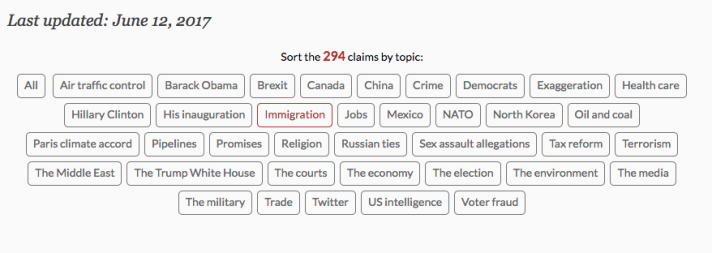

Despite my career as an “Applied Linguist,” I don’t feel that my job is to have strong opinions about language. Nor do I feel it is my professional role to resolve differences of opinion that inevitably arise about language, or to “debunk” certain opinions out of line with research-based studies. I am fascinated by other peoples’ opinions! And, I do care about people and what those opinions say–good and bad–about our society. Why are opinions about language so strong? What compels people to spend so much time and energy opining about, for example, the pretentiousness of “irregardless,” the dictionary-status of the word “ain’t”, the “ugliest” regional accent, or the proper way to speak “English” and when and where it should be used?

Even the most accomplished linguist cannot resolve these debates—at least not in their role as linguist. Why not? Isn’t scientific research the best way to seek truth, to push the world forward, and to promote progress and change for the better? Don’t linguists have the data that could resolve language debates? Yes and no.

While linguistics is sometimes categorized as a “science,” it differs in at least one important way from more prototypical scientific fields. Human language use (unlike our bio-chemical composition) is affected by opinions humans have about it. My cells are organized in a certain way that, as far as I know, will not be affected by what my opinion is about them. My own mother will always be my biological mother no matter what I think of her. But the way I speak—whether I call my mother “Mom,” “Ma,” “Mother,” or “Gretchen,” for example—is inevitably affected by my own opinions, my mother’s opinions, and the opinions of people around me, who hear me use those terms of address.

So, if peoples’ opinions about language affect how we talk and our opinions of other people’s talk, we probably can learn something about society by investigating those opinions more carefully—but what exactly can we learn? Let’s think that through.

First, take a basic opinion: English only!

As discussed in a previous post, statements about when and where English should be spoken might pose as reasonable requests for communicative clarity—but when looked at more carefully in context, they can also be a form of anti-immigrant racism, linguistic border patrol masquerading as reasonable opinions on language.

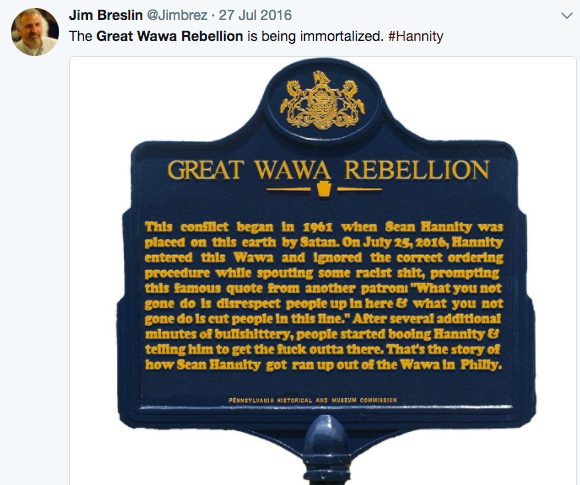

Language opinions also patrol less high-stakes borders. Consider, for example, the opinion that “the Philly accent is not the New York accent.” There are precise linguistic methods for measuring such a claim. However, stating this as an opinion may be more about establishing an identity as a Philadelphian than the phonological distinctions between a statistically significant sample of New Yorkers and Philadelphians—the opinion itself acts as a form of linguistic border patrol. And again, language itself may be a stand-in for other identity features that matter more.

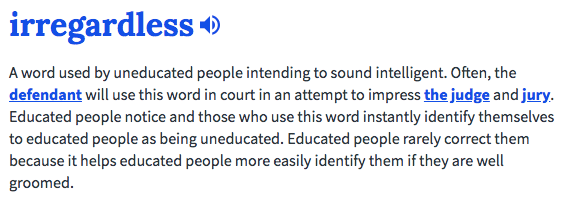

Sometimes, the linguistic border patrol sets up finer-grained distinctions, not about race, immigration status, or location: Consider the opinion, “Irregardless is not a word.” Whether or not this is a “word” matters far less to the person stating this opinion than the picture this word paints of the user. This “defininition” on Urban Dictionary provides a useful synopsis of what using “irregardless” might mean about someone:

The important border being guarded here seems to be between “educated” and “uneducated.”

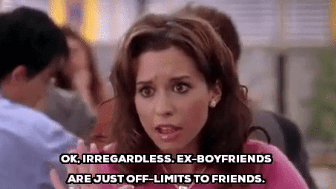

Another entry provides this useful clip from the movie “Mean Girls” to precisely illustrate a different type of person (one of the uncritical followers of the high school’s lead mean girl) who might use the word “irregardless”:

Views on languages, language varieties, and words like “irregardless,” (often fleshed out with supportive examples and illustrations) may start as “mere opinions” from “lay people” about language—but as they become conversations including more and more people (as tends to happen on the Internet), they also build knowledge about language. This knowledge isn’t validated through scientifically measurable accuracy of these descriptions—instead, this is a socially constructed accuracy. Language types called “English,” “Philly,” “New York,” or “Educated” become understood as these labeled entities because these opinions and conversations build portraits of language users as social types. The categories these citizen sociolinguists set up can act as self-fulfilling prophecies—building communities, setting up distinctions, or breaking them down.

What can we learn from this? We may not learn much about language at all—at least not the kind of learning you might expect from linguistics class or French101. But we can still learn something important. We can learn –through concrete discussions about language—how citizens shape distinctions between themselves and others, form local identities, create unique new identities, bond with and reject one another, and create and destroy social value. Once we glimpse these processes (through the work of citizen sociolinguists) we might not know more about language as an object, but we do have more awareness of how language builds meaning for everybody using it.

Have you come into contact with any strong opinions about language? What can you learn from those opinions? What social work do you think those opinions do? Please comment below.

In the United States, “

In the United States, “

happened on the card with the alphabet and learned how to spell our name, or to sign a few top secret words to friends. But after a first enthusiastic burst, the card gets lost, the signing seems like too much effort.

happened on the card with the alphabet and learned how to spell our name, or to sign a few top secret words to friends. But after a first enthusiastic burst, the card gets lost, the signing seems like too much effort.

How did Nyle respond? This seems like an important test of not only Deaf communication, but communication in general. According to a sign language interpreter friend of mine: “Nyle did apologize, saying he did not mean to take over and use his fame to overstep boundaries, and I don’t think this tainted his overall reception in any way.”

How did Nyle respond? This seems like an important test of not only Deaf communication, but communication in general. According to a sign language interpreter friend of mine: “Nyle did apologize, saying he did not mean to take over and use his fame to overstep boundaries, and I don’t think this tainted his overall reception in any way.”

Citizen Sociolinguists’ questions are constantly changing. One day, an important question to a particular citizen sociolinguist might be, “What is N

Citizen Sociolinguists’ questions are constantly changing. One day, an important question to a particular citizen sociolinguist might be, “What is N used it?”

used it?”  Often Citizen Sociolinguistic work involves using Social Media and the Internet, which means that Citizen Sociolinguists’ questions and findings constantly and speedily renew, change, and snowball with accumulated features of social context.

Often Citizen Sociolinguistic work involves using Social Media and the Internet, which means that Citizen Sociolinguists’ questions and findings constantly and speedily renew, change, and snowball with accumulated features of social context.

may or may not match with professional linguistic findings. These “folk” understandings about language may be disseminated to professional communities involved in teaching language or policy and planning. If, for example, Folk Linguistic studies reveal contradictory local impressions about certain dialect features, policy makers may need to know this before designing any specific curricula or rules about how those features should be discussed, mandated, or taught.

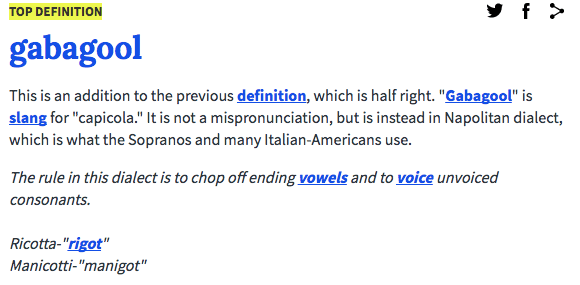

may or may not match with professional linguistic findings. These “folk” understandings about language may be disseminated to professional communities involved in teaching language or policy and planning. If, for example, Folk Linguistic studies reveal contradictory local impressions about certain dialect features, policy makers may need to know this before designing any specific curricula or rules about how those features should be discussed, mandated, or taught.  A couple weeks ago, I saw the item “gabagool” on the menu of a local Philly restaurant. Having lived in Philadelphia for a while, I had the vague feeling this was just an ironic nod to the way people here pronounce the delicious, ham-like meat, “Capicola.” But, since it was printed out on a real, official menu of a nice center city restaurant, I thought I might be mistaken. Maybe “gabagool” was just one more variation on Italian meats and cheeses that I didn’t know.

A couple weeks ago, I saw the item “gabagool” on the menu of a local Philly restaurant. Having lived in Philadelphia for a while, I had the vague feeling this was just an ironic nod to the way people here pronounce the delicious, ham-like meat, “Capicola.” But, since it was printed out on a real, official menu of a nice center city restaurant, I thought I might be mistaken. Maybe “gabagool” was just one more variation on Italian meats and cheeses that I didn’t know.

features of a scene that go into using the word “gabagool.” The most popular video example, by far, is

features of a scene that go into using the word “gabagool.” The most popular video example, by far, is

I don’t often mention the

I don’t often mention the  nitrous oxide and its various monikers? He clarifies: “…the popularity of the drug among teenagers at the turn of the century coincided with the release of The Fast and the Furious, a terrible film in which cars were customized to go faster with the addition of NOS (Nitrous Oxide Systems).”

nitrous oxide and its various monikers? He clarifies: “…the popularity of the drug among teenagers at the turn of the century coincided with the release of The Fast and the Furious, a terrible film in which cars were customized to go faster with the addition of NOS (Nitrous Oxide Systems).”