As all University researchers working with language know, if you record language, you must keep it in a locked filing cabinet or a password protected web location. For ethical reasons. Our Institutional Review Boards will insist on this.

As all University researchers working with language know, if you record language, you must keep it in a locked filing cabinet or a password protected web location. For ethical reasons. Our Institutional Review Boards will insist on this.

What (you may be wondering) is ethical about locking up language samples? Even keeping them from the speakers who created them? The idea is that if you are collecting talk from someone, you need to guard that “data” to protect the speakers from anything damning (embarrassing? false?) about them that those samples might reveal.

Only the researcher will still have access to this data. Ostensibly, in the role of a professional, with the training necessary to responsibly handle this language, the researcher will have the skills and knowledge to do the right thing, should they want to say something touchy about that language.

But, even as researchers lock up the drawer or type up a passcode for a website, people continue to talk. The voices we record for our research do not fall silent once we turn off the recording device.

Speech –our own and others’—is all around us. How do we protect those people from being interpreted in dangerous ways by the random ordinary people walking around judging how they speak? We don’t!

Fortunately, in real life we don’t need to hack into some password protected site to hear real language—or to analyze it.

We don’t even need to be professionally or academically affiliated in any way. Many people out there listening to the freely available language samples are expert language analysts. Their expertise may differ from that of a PhD Linguist, Applied Linguist, Sociologist, or Linguistic Anthropologist—but those everyday language analysts (I call them Citizen Sociolinguists) are not necessarily any more or less responsible in their interpretation of other peoples’ speech than a trained academic researcher.

Nor are those everyday analysts necessarily more or less tuned into their sense of ethical obligation toward speakers.

Nobody–University researchers or everyday opinionators—exclusively holds the ethical high ground when it comes to making statements about other peoples’ language.

Nobody has a premium on dumb or misguided interpretations—or on the most definitive explanation.

A good analogy might be the “Traditional Dictionary” versus “Urban Dictionary”. Which is most definitive? It depends on what you’re looking for and what sorts knowledge you care about.

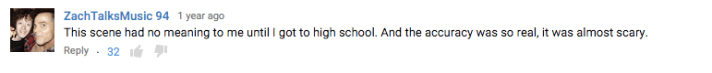

Similarly, “Sociolinguist” versus “Citizen Sociolinguist”: A sociolinguist may notice, measure, and catalogue discrete aspects of sound—but a citizen sociolinguist may notice identical features and simultaneously many other social features that go with those discrete linguistic bits: the types of people who use that type of speech, the way they dress, where they live, or personal stories and experiences with that bit of sound. Anyone can easily access these types of everyday insight by looking up questions about language on line. Google “How to speak like a _____” and you will encounter many examples of Citizen Sociolinguistic analysis—from the most raw to the most subtly incisive—and you will see many comments sounding off on the accuracy of these linguistic portraits.

Back to Locking up Language: When we officially gather and lock away some bits of language, we also place limits on our own knowledge, because we only let a few people interpret it and publish the results. Locked up language isn’t even available to the people who spoke it.

So, what to conclude?

I’d like to suggest an Open Source approach to language. If you record some, share it! And, certainly share it with the people who spoke it. But also share your analysis. Let ordinary speakers share theirs. Just as Open Source software improves when more coders are involved, understanding human language will inevitably become more important and relevant when it includes more perspectives. Tell that to your Institutional Review Board!

But—you may disagree. How might sharing language data be unethical? What might we lose in the open-source approach? What are other ways to ensure all language gets treated with respect? Please share your thoughts below!

Last week, the New York Times published an

Last week, the New York Times published an

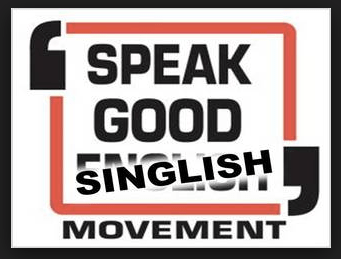

The Speak Good English movement also includes post-it note style signs like this, emphasizing the edits needed to “get it right”:

The Speak Good English movement also includes post-it note style signs like this, emphasizing the edits needed to “get it right”: I also started finding quite a few signs suggesting an underground “Speak Good Singlish” movement, and even a counter logo:

I also started finding quite a few signs suggesting an underground “Speak Good Singlish” movement, and even a counter logo:

Look around you and you will see all kinds of evidence that people like to agree!

Look around you and you will see all kinds of evidence that people like to agree!

Jane Frazee (a renowned music educator who also is my stepmother) has spent most of her life teaching and writing about music and music teachers (see her latest

Jane Frazee (a renowned music educator who also is my stepmother) has spent most of her life teaching and writing about music and music teachers (see her latest  notation. Why do we teach children to read music notes when their natural sense of rhythm and melody is always initially much more sophisticated than anything they can read on paper? Children who are jump-roping, hand-clapping, rapping, singing, patty-caking, Miss Mary Mack Mack Macking during recess, are looking at quarter notes and eighth notes in the music classroom and saying, in unison, “Ta Ta Tee Tee Ta.” Most children love music! But Music Class can seem disconnected from other experiences kids have making music. And as kids get older, into their teens, they want to be playing their own instruments, in bands with friends, or socializing around music in other ways that don’t seem to connect to more formal music instruction.

notation. Why do we teach children to read music notes when their natural sense of rhythm and melody is always initially much more sophisticated than anything they can read on paper? Children who are jump-roping, hand-clapping, rapping, singing, patty-caking, Miss Mary Mack Mack Macking during recess, are looking at quarter notes and eighth notes in the music classroom and saying, in unison, “Ta Ta Tee Tee Ta.” Most children love music! But Music Class can seem disconnected from other experiences kids have making music. And as kids get older, into their teens, they want to be playing their own instruments, in bands with friends, or socializing around music in other ways that don’t seem to connect to more formal music instruction. Have you ever tried crossposting?

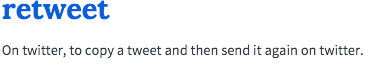

Have you ever tried crossposting? more generally. Crossposting—and its ramifications—as a metaphor for communication seems worth considering. What happens when you “crosspost” across the various social groups you are part of? Being completely oblivious of the participants and audience in each of these groups seems socially naïve—at best. And, this seems to be what happened at Yale last month, when professor Erika Christakis notoriously posted, to a college house e-mail listserve, the idea that Halloween is a chance to be “a little bit obnoxious,” countering the campus-wide e-mail suggesting students be sensitive about Halloween costumes (and, for example, avoid blackface). Bringing up the value of obnoxious Halloween costumes might be a nice debate on one of prof. Christakis’ “social media platforms”—say dinner with like-minded colleagues—but, as it turns out, it may be a dumb thing to crosspost to hundreds of Yale freshmen.

more generally. Crossposting—and its ramifications—as a metaphor for communication seems worth considering. What happens when you “crosspost” across the various social groups you are part of? Being completely oblivious of the participants and audience in each of these groups seems socially naïve—at best. And, this seems to be what happened at Yale last month, when professor Erika Christakis notoriously posted, to a college house e-mail listserve, the idea that Halloween is a chance to be “a little bit obnoxious,” countering the campus-wide e-mail suggesting students be sensitive about Halloween costumes (and, for example, avoid blackface). Bringing up the value of obnoxious Halloween costumes might be a nice debate on one of prof. Christakis’ “social media platforms”—say dinner with like-minded colleagues—but, as it turns out, it may be a dumb thing to crosspost to hundreds of Yale freshmen.