How do you translate talk and text? For many, Google Translate, the on-line translation robot, comes into play. But Google Translate makes mistakes, so ingenious humans have figured out nuanced ways of using it in not exactly the way it was intended: Google Translate hacks.

Hack #1: The Stereotype Detector

In this post on Google Translate one blogger asked “Is Google Translate Sexist?” and then suggested that, indeed, it is. He showed this by running tests in German, in which, for example, the word “teacher” in the phrase “Cooking teacher” translates as “Lehrerin” (feminine) while in “Math teacher” it translates as “Lehrer” (masculine).

I tested this myself, with Spanish: Sure enough, a “Cooking teacher” is a “professora” (feminine), while a “Math teacher” is a “professor” (Masculine).

This does not necessarily mean Google Translate is sexist. Instead, this “sexist” translation illustrates Google Translate’s strength as a potential stereotype detector. Some words collect in gendered ways. We recognize these stereotypes—in concert with Google Translate.

Hack #2: The Bilingual Expertise Detector

In the transcript below, from Meredith Byrnes’ research on bilingual family literacy, a bilingual mother is explaining to her two boys (ages five and six) how she translates the English idiom, “school of fish”:

¡Porque aquí dice school of fish y abajo dice banco de pescado. Pero si fuera- si como dice arriba school of fish seria escuela de pescado!

(Because here it says school of fish and down here it says bank of fish. But if it was- if it says school of fish it would be school of fish!)

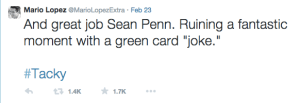

Bilingual people like this mom have special knowledge. The boys will not be able to simply use word by word translation or a dictionary or even Google Translate for an idiom, because it does not translate literally:

Nope! Google Translate doesn’t get it. But this “mistake” reveals how Google Translate can work well as a Citizen Sociolinguistic tool. In its dumb errors (or “sexist” oversteps) Google Translate can reveal the nuanced knowledge of human beings, like this bilingual mom.

Hack #3: The Bilingual Collective Expertise Detector

Flash forward 10 years in the life of a bilingual family. Often, bilingualism is distributed across a family, parents having expertise in one language, children in another. Robert LeBlanc’s research on multilingual literacy among teens who attend a massively multilingual Catholic Church (services offered in English, Spanish, Vietnamese, and Tagalog) illustrates this point. And, he learned about this Google Translate hack one family developed there.

Teens who attend this church regularly use Google Translate as just one of several translation steps to read scripture publically. One teen, who doesn’t speak much Vietnamese, or read any, manages to recite scripture aloud in church. These are his basic steps:

- Types bible passage into Google Translate

- Prints out Vietnamese text from Google Translate

- Asks mother (who speaks and writes in Vietnamese, but not English) to edit, smoothing over the inevitable Google Translate errors.

- Records mother reading the passage aloud, using his phone.

- Listens to audio from phone during spare moments and repeats it until it is committed to memory.

- Recites memorized Vietnamese bible passage in church.

With this hack, Google Translate, which seems impersonal and error-prone, has the potential to function as an intimate medium, forcing at least one teen to engage deeply on a multilingual task with his mother.

Lost and Found in Google Translation

Because Google Translate is imperfect, much is lost in translation. But when we use Google Translate as Citizen Sociolinguists, in concert with multilingual acquaintances, friends, or family members, much more can be found. How do you use Google Translate? What Google Translate hacks do you know? Please share and comment below!