You may think pronouncing UGG is as easy as saying “AHH” when you slip your foot into the cushy sheepskin lined interior of an UGG boot. It is! But, in happy citizen sociolinguistic fashion, there is more than one way to do it.

I discovered this recently when a student pointed out (literally spelled out) that she was wearing some cozy “U-G-G” boots, treating UGG as an initialism, like UCLA or FBI. My citizen sociolinguistic senses were tingling, so I had to ask the class: Do you all say U-G-G, not “Ugh”? The Chinese speakers in the class nodded, and one provided an explanation: The word “Ugh” is difficult to say for Chinese speakers. U-G-G is much easier.

Another student explained that the sound “ugh” had a meaning in Chinese so saying U-G-G instead circumvents any confusion. (This explanation was not whole-heartedly endorsed by other Chinese speakers in the class).

I was curious what Internet AI would say. My computer’s “AI Overview” had a very firm anti-U-G-G stance: UGG is pronounced like “hug” without the h.

AI OVERVIEW: You say “Ugg” like the word “hug,” but without the ‘h’ sound at the beginning; it’s a single syllable, rhyming with “bug” or “mug,” often pronounced closer to “uh-g” or even “ag” in Australia, the boot’s origin. It’s pronounced as one sound, not “U-G-G”.

Consistent with this “overview” there are many YouTube videos demonstrating how to pronounce UGG “in English.” Most go with “ugh” and a few illustrate the Australian pronunciation (“ag,” as in “agriculture”) also mentioned in the AI Overview. I found no demos of “U-G-G.”

But apparently someone else was UGG-curious eight years ago and posted this question on Quora, “Why do Chinese spell “U-G-G-S” instead of just saying “Uggs”?” The lone responder wrote, “Because they assume it’s an abbreviation like NBA.” (Who’s assuming now?!). After assuming this rationale, the lone responder continued: “The funny thing is, they stick to this pronunciation, even when you tell them the ‘correct’ way. What’s funnier is that the Australian customs officers have got used to saying ‘U-G-G’ to make sense to the Chinese visitors.”

This anecdote endears me to these pragmatic Australian customs officers/citizen sociolinguists! But it seems a bit dismissive of the U-G-G pronunciation (as funnily persistent “even when you tell them the ‘correct’ way”) and it fails to mention my Chinese-speaking students’ explanation about the difficulty and possible weirdness of saying “ugh” instead of U-G-G.

I encountered a new take when I came across a TikTok post, “How do French people pronounce “UGG”? This is nothing like “hug without an h”—it’s more like something you might say when looking out from your Parisian garret at a glittering Eiffel Tower and popping a bottle of the best Champagne. “Oo Jey Jey!”

Click on this link to hear for yourself this fabulous UGG pronunciation:https://www.tiktok.com/@masha_in_paris/video/7172919774341614853

Let’s sum up: Chinese speakers seem to favor “U-G-G.” French speakers, “oo-jey-jey”. Aussies say “ag”. Internet AI and most YouTube tutorials say “Ugh.” Are all these pronunciations okay? I think so. UGG is not an “English” word—it’s a brand name! So, give yourself this holiday gift: Enjoy your favorite pronunciation as you would your favorite Aussie sheepskin slipper. From this point forward I will be luxuriating in my own imaginary pair of Oo Jey Jeys. Oolala!

Have you encountered any surprisingly wonderful new pronunciations lately? Please share below!

Last week, the New York Times published an

Last week, the New York Times published an

The Speak Good English movement also includes post-it note style signs like this, emphasizing the edits needed to “get it right”:

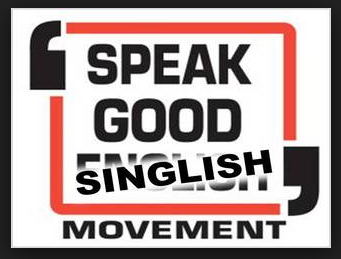

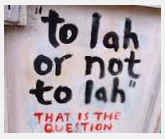

The Speak Good English movement also includes post-it note style signs like this, emphasizing the edits needed to “get it right”: I also started finding quite a few signs suggesting an underground “Speak Good Singlish” movement, and even a counter logo:

I also started finding quite a few signs suggesting an underground “Speak Good Singlish” movement, and even a counter logo: