The term “Malapropism” describes a lovable feature of our all-too-human use of language—that is, using the almost-right-but-not-quite-right word. YourDictionary.com illustrates their entry with this example, spoken by the TV character, Archie Bunker:

“Patience is a virgin.”

This example illustrates the layers of possibility within subtle linguistic missteps. In choosing the words “patience is a virgin” instead of “patience is a virtue” the script-writers pile on a little jokey sexual innuendo and maybe a touch of creepy-old-man, building Archie Bunker’s character as a conservative curmudgeon in the decades-old sitcom, All in the Family.

A good malapropism—like any good joke—may also go down in history. Everyday people seem to remember them and pass them along. Something about them draws people to savor the language, to recognize its special capacity for creative meaning, and even to make fun of ourselves and the human condition.

The baseball coach, Yogi Berra, was famous for his malapropisms (or “Yogiisms”), and for their humor and everyday pithy wisdom. Phrases like “It ain’t the heat, it’s the humility,” “Nobody goes there anymore, it’s too crowded,” or “When you get to a fork in the road, take it” bring home some shared sense of the absurdity of everyday life. Rather than bringing out the dictionary and calling Yogi to the mat for being incorrect or nonsensical, people have ended up repeating these Yogiisms-turned-aphorisms. An internet search yields dozens of sites compiling his top 20 (or 50!) phrases.

their humor and everyday pithy wisdom. Phrases like “It ain’t the heat, it’s the humility,” “Nobody goes there anymore, it’s too crowded,” or “When you get to a fork in the road, take it” bring home some shared sense of the absurdity of everyday life. Rather than bringing out the dictionary and calling Yogi to the mat for being incorrect or nonsensical, people have ended up repeating these Yogiisms-turned-aphorisms. An internet search yields dozens of sites compiling his top 20 (or 50!) phrases.

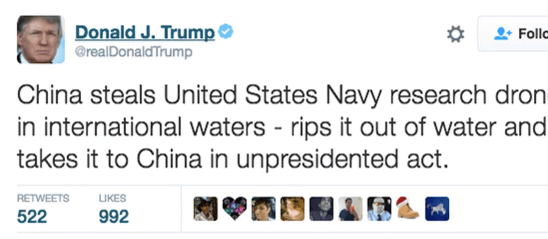

Now, Donald Trump has become a modern proliferator of malapropisms:

Unpresidented or Unprecedented When condemning China’s actions in international waters, he referred to their actions as “unpresidented”:

7/11 (The convenience store?) versus 9/11 During his presidential campaign, he denounced the terror attacks on the World Trade Center—those that occurred on “Seven Eleven.”

“I watched our police and our firemen down on 7/11, down on the World Trade Center before it came down.”

Bigly versus Big League Also during his campaign, Trump repeatedly used the term “bigly.” Though his handlers claimed he was saying “big league,” this odd usage stood out so prominently to citizens that memes around “bigly” have proliferated…bigly.

There are probably more, and more serious malapropisms in Trump’s repertoire. But even this short list suggests a qualitative difference between Trump’s malapropisms and Yogi Berra’s—or even Archie Bunker’s. Trump’s seem worse.

But, if malapropisms aren’t inherently bad, what exactly is wrong with Trumpisms?

It’s not that they are “poor English.” Many people have written about how Trump abuses the English language. Some have catalogued Trump’s malapropisms as “Times when the English language took a hit”. But abuse of the English language is not the real problem here.

The problem isn’t that Trump uses words in unorthodox ways, but the precise quality of the missteps he makes. They show none of the qualities of time-tested malapropisms—humor or tacit wisdom. Granted, the 7/11 gaff may have dark humor to it. But, generally, Trumpisms are not funny. He certainly has no sense of humor about them. In fact, he often tries to correct them immediately by removing tweets (like the “unpresidented” tweet above) as soon as he’s been called out. Trumpisms shed no wisdom or whimsical perspective on the human condition. The only tacit message they communicate is (at best) that he doesn’t really care that much. And no amount of time with a dictionary, grammar book, or linguistics professor will cure that.

Good news: Despite Trump’s use of bigly, unpresidented, 7/11 (for 9/11), and probably many more absurdities, the English language is safe. Trump may spew malapropisms, but malapropisms in themselves are not bad—they show us that language is alive and inevitably unorthodox at times. Every day, people use words in ways which create new (unpresidented?) meanings.

And who knows, maybe soon we will be unpresidented! Patience is a virgin.

Please add your comments below! Do you have malapropisms you love or hate? Any recent Trumpisms to add? What can we learn from these?

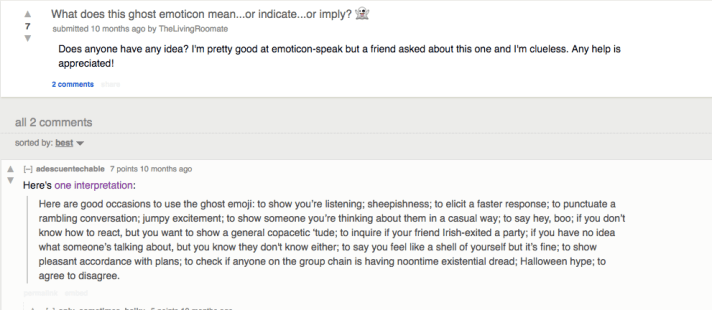

Have you ever sent or received a ghost emoji? What does it mean? This is a perfect question for the Citizen Sociolinguist—because we can only answer it by asking what citizens-who-use-ghost-emojis say about it.

Have you ever sent or received a ghost emoji? What does it mean? This is a perfect question for the Citizen Sociolinguist—because we can only answer it by asking what citizens-who-use-ghost-emojis say about it. Sound familiar? This response is a direct link back to the GQ article I previously mentioned.

Sound familiar? This response is a direct link back to the GQ article I previously mentioned.

alism. A google image search yields images representing anarchy as associated with liberty, peace, collaboration, freedom, and mutualism. Rather than relying on overt violence, anarchism usually flies below the radar. It’s tricky, often clever, and often (for example, in cases of poaching or squatting) a matter of survival.

alism. A google image search yields images representing anarchy as associated with liberty, peace, collaboration, freedom, and mutualism. Rather than relying on overt violence, anarchism usually flies below the radar. It’s tricky, often clever, and often (for example, in cases of poaching or squatting) a matter of survival. quotidian form of politics available” (p. 12).

quotidian form of politics available” (p. 12). Have you ever had to transcribe oral speech?

Have you ever had to transcribe oral speech?

As all University researchers working with language know, if you record language, you must keep it in a locked filing cabinet or a password protected web location. For ethical reasons. Our Institutional Review Boards will insist on this.

As all University researchers working with language know, if you record language, you must keep it in a locked filing cabinet or a password protected web location. For ethical reasons. Our Institutional Review Boards will insist on this. Last week, the New York Times published an

Last week, the New York Times published an

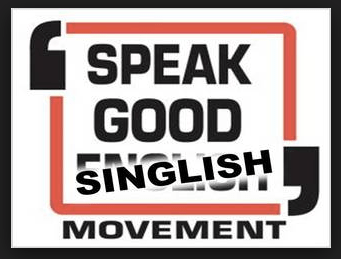

The Speak Good English movement also includes post-it note style signs like this, emphasizing the edits needed to “get it right”:

The Speak Good English movement also includes post-it note style signs like this, emphasizing the edits needed to “get it right”: I also started finding quite a few signs suggesting an underground “Speak Good Singlish” movement, and even a counter logo:

I also started finding quite a few signs suggesting an underground “Speak Good Singlish” movement, and even a counter logo:

Look around you and you will see all kinds of evidence that people like to agree!

Look around you and you will see all kinds of evidence that people like to agree!

Jane Frazee (a renowned music educator who also is my stepmother) has spent most of her life teaching and writing about music and music teachers (see her latest

Jane Frazee (a renowned music educator who also is my stepmother) has spent most of her life teaching and writing about music and music teachers (see her latest  notation. Why do we teach children to read music notes when their natural sense of rhythm and melody is always initially much more sophisticated than anything they can read on paper? Children who are jump-roping, hand-clapping, rapping, singing, patty-caking, Miss Mary Mack Mack Macking during recess, are looking at quarter notes and eighth notes in the music classroom and saying, in unison, “Ta Ta Tee Tee Ta.” Most children love music! But Music Class can seem disconnected from other experiences kids have making music. And as kids get older, into their teens, they want to be playing their own instruments, in bands with friends, or socializing around music in other ways that don’t seem to connect to more formal music instruction.

notation. Why do we teach children to read music notes when their natural sense of rhythm and melody is always initially much more sophisticated than anything they can read on paper? Children who are jump-roping, hand-clapping, rapping, singing, patty-caking, Miss Mary Mack Mack Macking during recess, are looking at quarter notes and eighth notes in the music classroom and saying, in unison, “Ta Ta Tee Tee Ta.” Most children love music! But Music Class can seem disconnected from other experiences kids have making music. And as kids get older, into their teens, they want to be playing their own instruments, in bands with friends, or socializing around music in other ways that don’t seem to connect to more formal music instruction. Have you ever tried crossposting?

Have you ever tried crossposting? more generally. Crossposting—and its ramifications—as a metaphor for communication seems worth considering. What happens when you “crosspost” across the various social groups you are part of? Being completely oblivious of the participants and audience in each of these groups seems socially naïve—at best. And, this seems to be what happened at Yale last month, when professor Erika Christakis notoriously posted, to a college house e-mail listserve, the idea that Halloween is a chance to be “a little bit obnoxious,” countering the campus-wide e-mail suggesting students be sensitive about Halloween costumes (and, for example, avoid blackface). Bringing up the value of obnoxious Halloween costumes might be a nice debate on one of prof. Christakis’ “social media platforms”—say dinner with like-minded colleagues—but, as it turns out, it may be a dumb thing to crosspost to hundreds of Yale freshmen.

more generally. Crossposting—and its ramifications—as a metaphor for communication seems worth considering. What happens when you “crosspost” across the various social groups you are part of? Being completely oblivious of the participants and audience in each of these groups seems socially naïve—at best. And, this seems to be what happened at Yale last month, when professor Erika Christakis notoriously posted, to a college house e-mail listserve, the idea that Halloween is a chance to be “a little bit obnoxious,” countering the campus-wide e-mail suggesting students be sensitive about Halloween costumes (and, for example, avoid blackface). Bringing up the value of obnoxious Halloween costumes might be a nice debate on one of prof. Christakis’ “social media platforms”—say dinner with like-minded colleagues—but, as it turns out, it may be a dumb thing to crosspost to hundreds of Yale freshmen.