Did you LEARN how to speak English or ACQUIRE that ability? What about Spanish? Or Arabic? This is a distinction that many in the language teaching world like to think about.

Some tend to think that first languages (“mother tongues”) are acquired through participation in family and society, while additional languages require explicit instruction, and are thus learned. Nobody taught us how to conjugate verbs as we acquired our first language—but this seems to be a big focus of learning additional languages in high school.

But even granting that you acquired a lot as a baby, don’t you consciously continue to learn a lot about your own “mother tongue” as you get older? Consider all the subtle forms of language we continue to learn/acquire long after we seem to have mastered at least one “mother tongue.” Some of that later-in-life language we acquire without much thought, but other language, we probably spend some conscious effort learning.

Take, for example, ordering a hoagie (sandwich) at Wawa. If you are not from greater Philadelphia, you may not even know what I’m talking about. For many, this type of language knowledge has been acquired through such subtle cumulative processes of socialization that people don’t know how to articulate it. And, it may feel awkward to ask someone directly how to order a hoagie at Wawa. So, it seems better to just muddle along in the hopes that finally you’ll get it (acquire it).

But sometimes we just don’t have the time, the connections, or the guts to acquire certain types of language knowledge through incremental interactional trial-and-error.

That’s where Citizen Sociolinguists come in.

This act of articulating subtle, socioculturally acquired knowledge—so that outsiders can learn it— is PRECISELY what Citizen Sociolinguists do. You want to know how to order a sandwich at Wawa? Citizen Sociolinguists have produced You Tube videos on it:

Not even sure what “Wawa” means? You don’t have to wait through years of socialization to acquire that knowledge, you can simply google it. If you look on Urban Dictionary, you can get a relatively straight definition:

Etc…

And, if you browse through other definitions, you will also get a taste for the ironic reverence many Philadelphian’s feel for the convenience store:

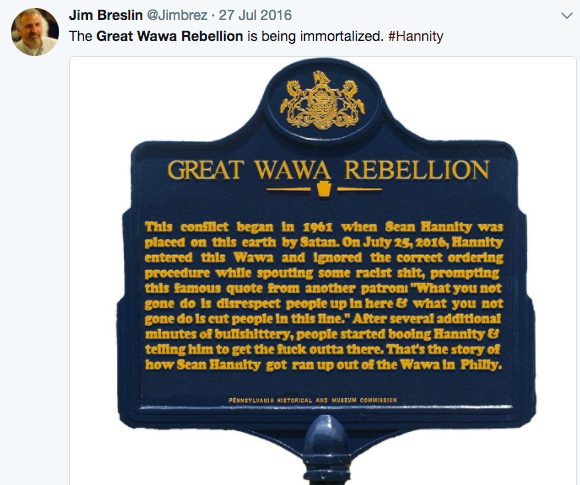

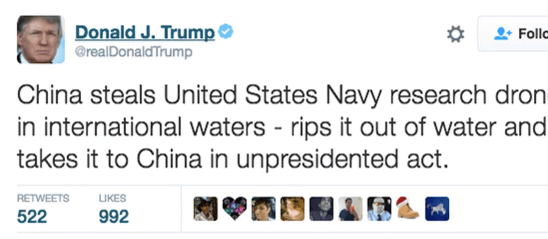

You can also browse a bit and find some good stories of people who did not follow protocol at Wawa, like this Twitter post featuring a gaffe by Sean Hannity (woe is he):

Citizen Sociolinguists then, are the language teachers you always wish you had—the ones who teach you what is NOT in the book, but what is crucial to learn to get along. The ones who answer the questions you were afraid to ask—because it seems like you are supposed to already “just know.”

This explicit learning provides a good starting point—by directing language learners (all of us) what to look for. Once I get some explicit instruction on, say, “how to order a sandwich at Wawa” or, for that matter, “how to greet someone on the street in Philadelphia,” I don’t need to follow those explicit steps, but I may begin to notice how true-to-life this depiction is—or how people vary from it—and how my own individual variation may fit in.

Citizen Sociolinguists provide us the secrets all good teachers do—combatting a fear of total ignorance that might otherwise paralyze a learner—so that we can forge ahead on our own learning path.

By the way, many contemporary applied linguists and language teachers avoid both the terms “learning” and “acquisition” in favor of “language development”—a combination of these processes. This also seems to apply to the type of growth that happens when we engage with Citizen Sociolinguists.

How have you used the Internet and the knowledge of Citizen Sociolinguists to learn a new language, or to learn new aspects of a language you’ve been struggling to understand? Has this explicit training opened new forms of participation for you? Please leave your comments below!

I don’t often mention the

I don’t often mention the  nitrous oxide and its various monikers? He clarifies: “…the popularity of the drug among teenagers at the turn of the century coincided with the release of The Fast and the Furious, a terrible film in which cars were customized to go faster with the addition of NOS (Nitrous Oxide Systems).”

nitrous oxide and its various monikers? He clarifies: “…the popularity of the drug among teenagers at the turn of the century coincided with the release of The Fast and the Furious, a terrible film in which cars were customized to go faster with the addition of NOS (Nitrous Oxide Systems).”

their humor and everyday pithy wisdom. Phrases like “It ain’t the heat, it’s the humility,” “Nobody goes there anymore, it’s too crowded,” or “When you get to a fork in the road, take it” bring home some shared sense of the absurdity of everyday life. Rather than bringing out the dictionary and calling Yogi to the mat for being incorrect or nonsensical, people have ended up repeating these Yogiisms-turned-aphorisms. An internet search yields dozens of sites compiling his top 20 (or 50!) phrases.

their humor and everyday pithy wisdom. Phrases like “It ain’t the heat, it’s the humility,” “Nobody goes there anymore, it’s too crowded,” or “When you get to a fork in the road, take it” bring home some shared sense of the absurdity of everyday life. Rather than bringing out the dictionary and calling Yogi to the mat for being incorrect or nonsensical, people have ended up repeating these Yogiisms-turned-aphorisms. An internet search yields dozens of sites compiling his top 20 (or 50!) phrases.

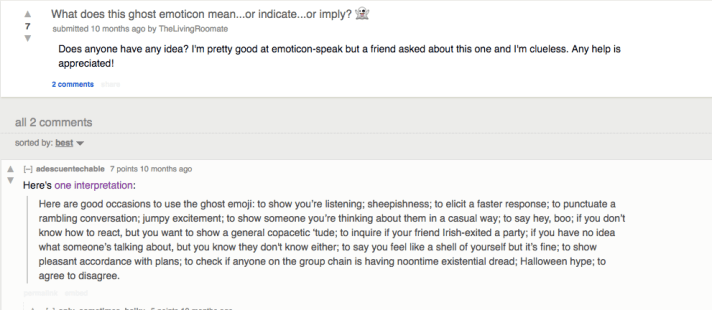

Have you ever sent or received a ghost emoji? What does it mean? This is a perfect question for the Citizen Sociolinguist—because we can only answer it by asking what citizens-who-use-ghost-emojis say about it.

Have you ever sent or received a ghost emoji? What does it mean? This is a perfect question for the Citizen Sociolinguist—because we can only answer it by asking what citizens-who-use-ghost-emojis say about it. Sound familiar? This response is a direct link back to the GQ article I previously mentioned.

Sound familiar? This response is a direct link back to the GQ article I previously mentioned.

alism. A google image search yields images representing anarchy as associated with liberty, peace, collaboration, freedom, and mutualism. Rather than relying on overt violence, anarchism usually flies below the radar. It’s tricky, often clever, and often (for example, in cases of poaching or squatting) a matter of survival.

alism. A google image search yields images representing anarchy as associated with liberty, peace, collaboration, freedom, and mutualism. Rather than relying on overt violence, anarchism usually flies below the radar. It’s tricky, often clever, and often (for example, in cases of poaching or squatting) a matter of survival. quotidian form of politics available” (p. 12).

quotidian form of politics available” (p. 12). Have you ever had to transcribe oral speech?

Have you ever had to transcribe oral speech?

As all University researchers working with language know, if you record language, you must keep it in a locked filing cabinet or a password protected web location. For ethical reasons. Our Institutional Review Boards will insist on this.

As all University researchers working with language know, if you record language, you must keep it in a locked filing cabinet or a password protected web location. For ethical reasons. Our Institutional Review Boards will insist on this. Last week, the New York Times published an

Last week, the New York Times published an

The Speak Good English movement also includes post-it note style signs like this, emphasizing the edits needed to “get it right”:

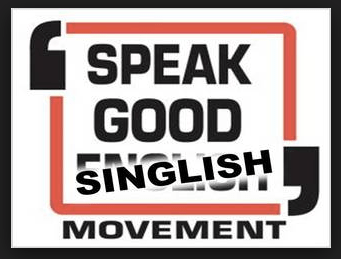

The Speak Good English movement also includes post-it note style signs like this, emphasizing the edits needed to “get it right”: I also started finding quite a few signs suggesting an underground “Speak Good Singlish” movement, and even a counter logo:

I also started finding quite a few signs suggesting an underground “Speak Good Singlish” movement, and even a counter logo:

Look around you and you will see all kinds of evidence that people like to agree!

Look around you and you will see all kinds of evidence that people like to agree!